From Spectacle to Stillness: Kate Moss for Calvin Klein

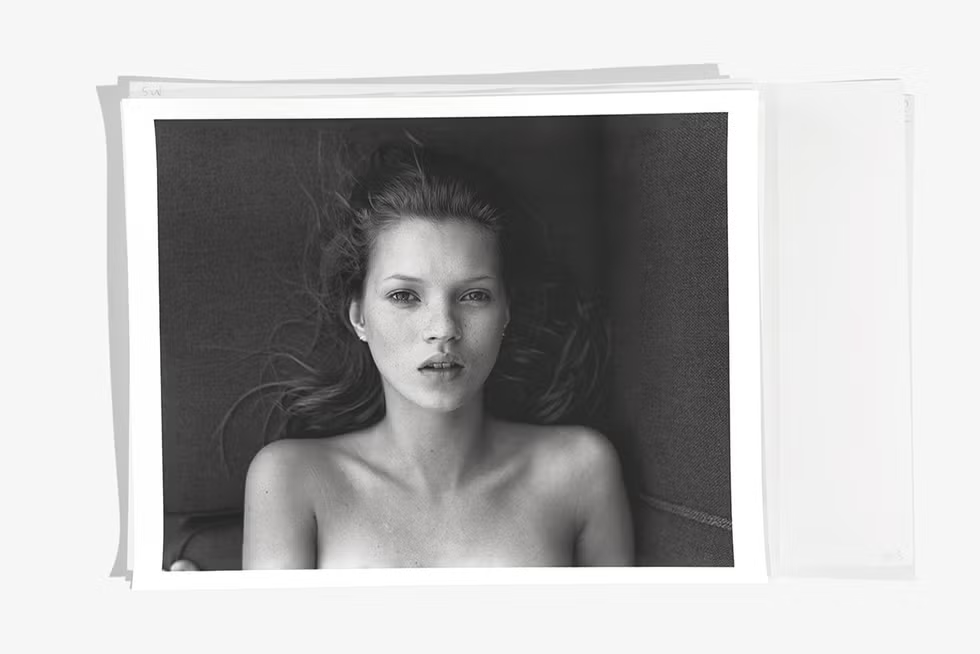

Kate Moss for Calvin Klein ‘Obsession’ campaign, 1993; Photo by: Mario Sorrenti

From Spectacle to Stillness: Kate Moss for Calvin Klein

There are always two players in fashion: those who craft the image and those who become it. In 1993, Moss, then 18 and barely known outside of London’s casting rooms, stepped into Calvin Klein’s Obsession frame, and something changed; a campaign that would rewire the visual vocabulary of the decade. No gloss. No spectacle. Shot in grainy black and white, she stares directly into the lens, not quite smiling, not quite styled. “Be good. Be bad. Just be.” the campaign whispered. And with that, fashion seemed to listen: shedding ornament for honesty, polish for presence.

Together, Klein and Moss created a new kind of space where style was not performed but inhabited — a quiet dialogue between body and image, self and silence.

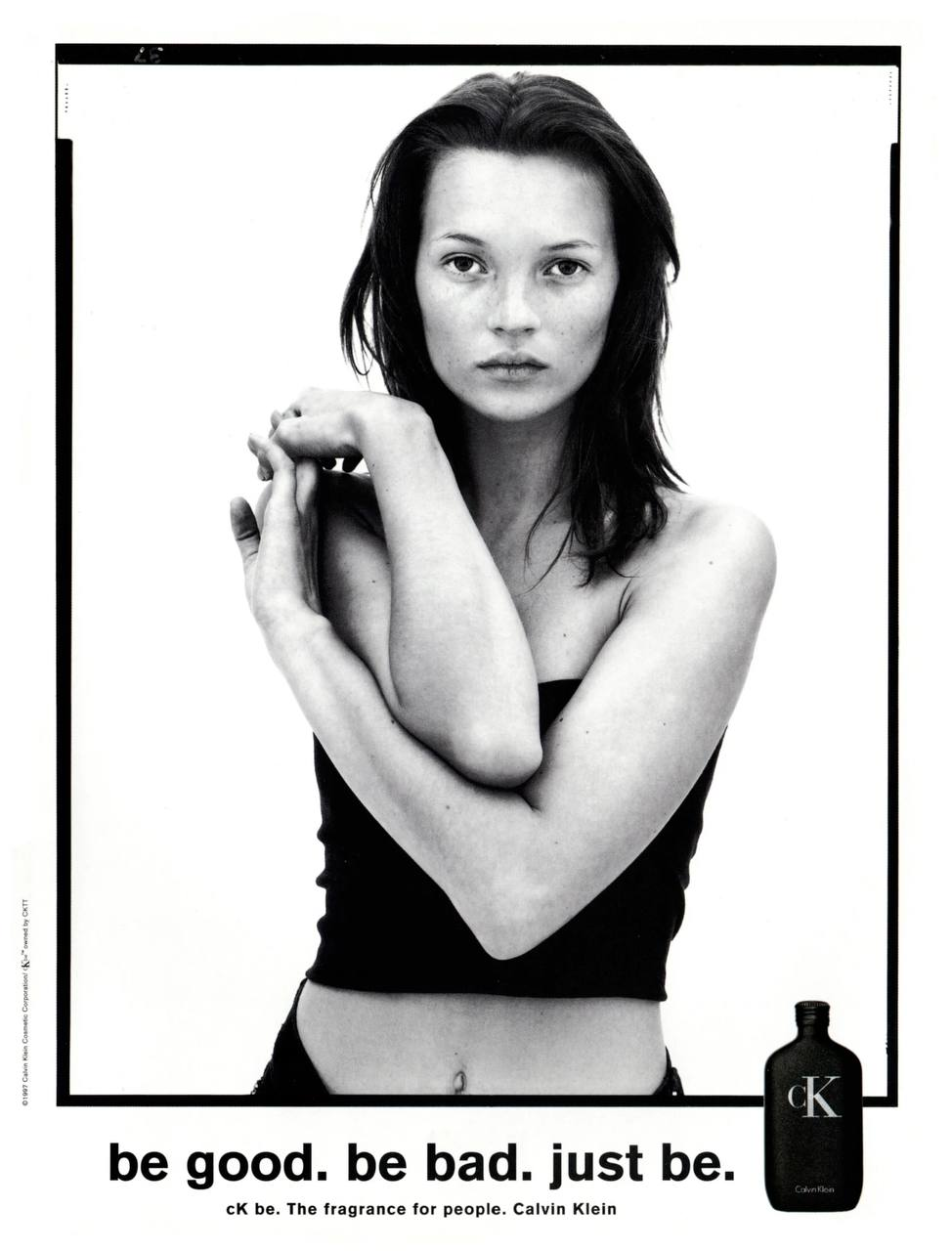

Kate Moss for Calvin Klein Fragrance, 1997; Photo by: Richard Avedon

By the end of the 1980s, fashion had reached a visual saturation point – a crescendo of spectacle where more was never quite enough. The dominant look was sculptural and excessive: shoulder pads carved power, lips lacquered red, and supermodels moved like sirens across glimmering sets. But the ’90s arrived with restraint. Economic recession, generational fatigue, and a growing disillusionment with high-octane luxury reshaped the cultural appetite, as minimalism, introspection, and aesthetic neutrality began to take hold.

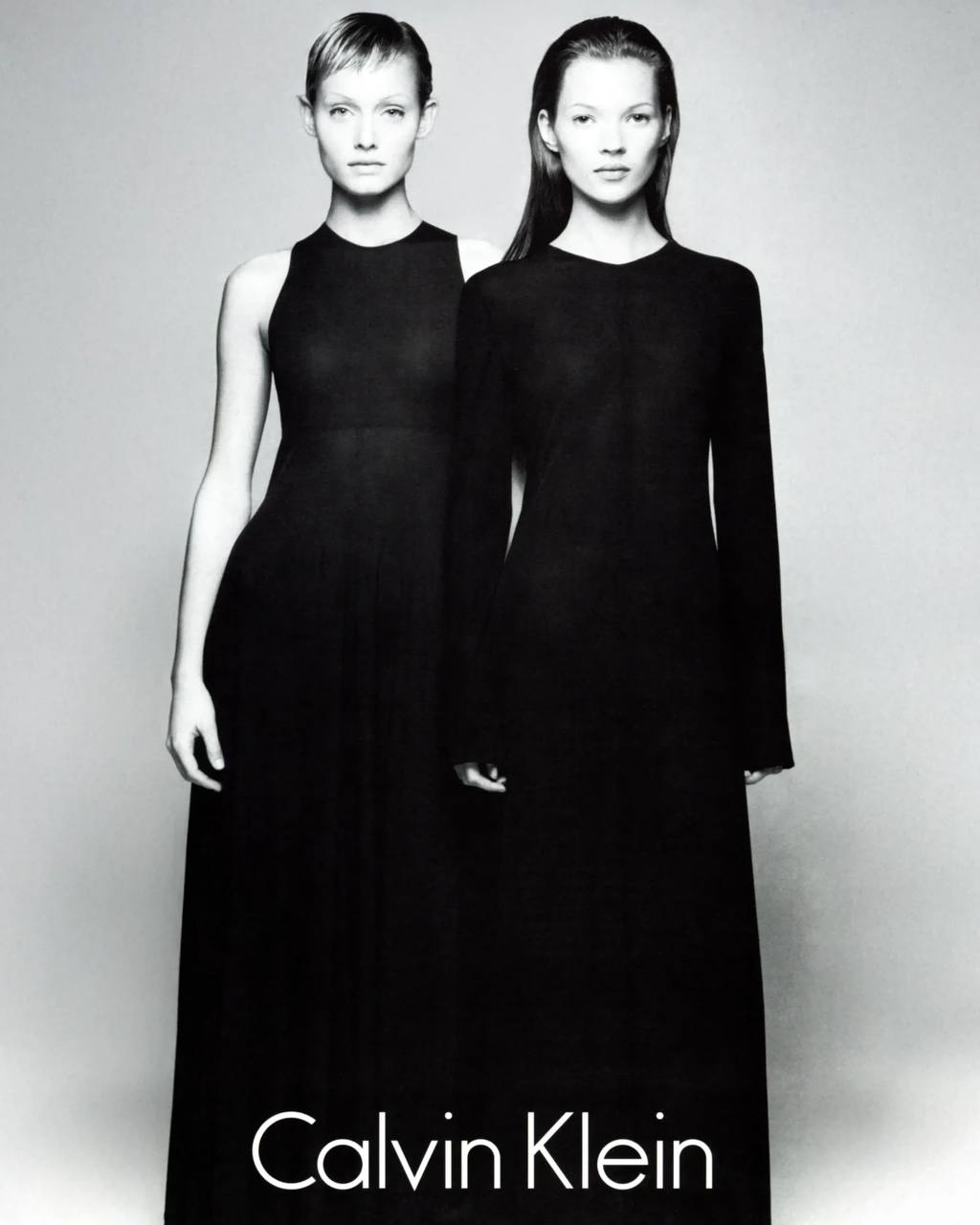

Calvin Klein was already fluent in this language. But his vision of minimalism was never sterile. His garments weren’t about silence for its own sake; they were about feeling. Sheer slip dresses, understated tailoring, and pared-down denim made up a wardrobe built on instinct, not display. He believed in clothes that reflected how women lived. This was not a rejection of glamour, but a distillation of it.

With each season, the message became more refined. The tailoring loosened. The silhouette softened. “Pure and wearable, yet never dull and safe,” Klein said of his work. These were clothes that moved with the body rather than around it. His mid-90s collections captured this fully: soft, sensual, and quietly confident. “It’s always been spare,” he reflected. “It’s always been about sensuality. And above all, it always represented what I think is modern.”

Photo by: Lynn Karlan for Women’s Wear Daily, September 26, 1976.

Kate Moss stepped into this world not as a disruption, but as its logical extension. Her presence didn’t complete the image — it revealed it. Her debut in the 1992 Calvin Klein campaign didn’t merely reflect a visual shift; it crystallized it. The images, stark in black and white, felt both immediate and unfinished. The campaign’s tension culminated in her now-infamous jeans ad with Mark Wahlberg. He, shirtless and sculpted. She, topless in denim, her body dissolving into the frame. The reaction was instant, the campaign was met with moral criticism and commercial success. But it left behind a more enduring impression: a new visual rhetoric for fashion. One that no longer relied on performance or perfection, but on suggestion, ambiguity, and tone.

Kate Moss for Calvin Klein Underwear, 1993; Photo by: Devid Sims

Moss appeared both passive and composed, exposed yet untouchable. What she and Klein mapped was a new aesthetic — one rooted in purity, seduction, and identity. A visual language deeply entangled with body politics, anti-glamour, and the minimalist mood of the 1990s.

Where once the supermodel represented aspiration, Moss offered ambiguity. Pale, androgynous, hollow-eyed — her image disrupted the dominant codes of desirability. Critics labelled it “heroin chic,” a term coined by media to describe the waifish aesthetic and subdued mood emerging in '90s fashion imagery. But the phrase flattens what was actually taking place. Moss didn’t glamorise fragility; she exposed a shift. That beauty could feel uncomfortable, even confrontational. That mood could be just as powerful as form.

Kate Moss and Amber Valletta, 1993; Photo by: Richard Avedon

Today, the echoes of that aesthetic still remain. Photographers moved away from mythic glamour and toward mood. Grain, blur, shadow, suggestion. The industry shifted from glossy, posed perfection to a kind of documentary-like realism. Brands stopped asking for beauty alone. They began to ask for emotion.

What Moss and Klein shaped was not just a campaign, but a vocabulary: spare, suggestive, impossible to forget.

Looking back, the Klein–Moss moment was not merely a branding success or a cultural controversy. It was a turning point. A moment when minimalism became assertive, when beauty became less about allure and more about attitude. A moment when fashion, once fluent in spectacle, began to speak in a lower voice. Its resonance endures — resurfacing in each cyclical return to restraint, where shifts in beauty standards and consumer appetite echo the same quiet rebellion Moss once made visible.