For Her, By Him: When Fashion’s Feminine Ideal Is Man-Made

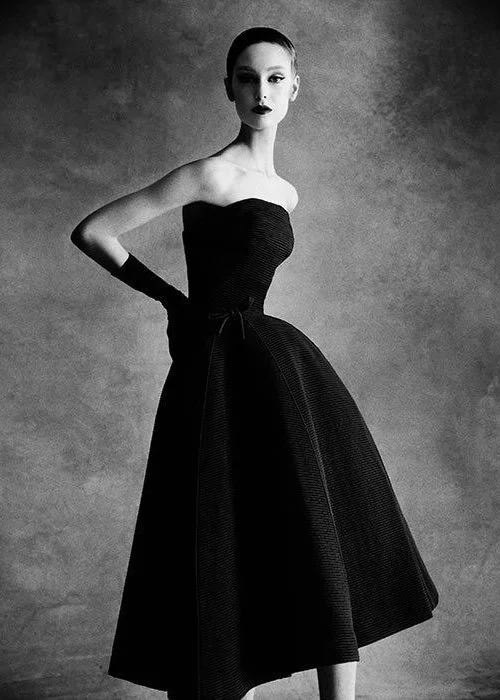

Dior by Christian Dior, 1947

For Her, By Him: When Fashion’s Feminine Ideal Is Man-Made

In the mythology of fashion, few things are more revered than the man who “understands women.” He’s not only dressing the female figure, he shapes, sculpts, and celebrates it. He just seems to get women. Or so the narrative goes. From Valentino Garavani’s timeless allure to Gianni Versace’s bold sensuality the legacy of menswear-designed womenswear has long been romanticized as a form of benevolent mastery. But in a moment when fashion is reckoning with gendered gaze and a grappling of power, it’s worth asking: who does this understanding really serve?

This legacy of him-for-her in fashion runs deep and is well documented. Christian Dior's 1947 collection “New Look”, which effectively redefined postwar femininity, was described as a “return to elegance” in a world starved of beauty. His full skirts and cinched waists promised luxury and softness, recentering the feminine ideal of domesticity wrapped in layers of tulle. Similarly, Oscar de la Renta’s regal evening wear became a staple for women of a certain class and stature, a kind of upper-crust sensuality that never claimed to be radical, only refined. Alexander McQueen, often cited for his tortured yet exquisite approach to the female form, offered silhouettes both aggressive and reverent. His designs were emotional, sometimes disturbing, and always grand.

These men, like many others, were and are praised for their “intimacy” with the female body. But lately, a phrase has been making its rounds online, sparking discourse and slicing through this myth with something sharper. Montage-style videos of male designers' best work overlaid with the phrase “You can tell if a designer loves women by their designs”. It reads as less critique than gut check, and once you hear it, you can’t unsee it. It’s there in the way a dress constricts or releases, in who the silhouette was made for, in what kind of femininity is being celebrated or subdued.` It also hinges on an idea of femininity that is shaped, quite literally, by someone else.

(Krizia – SS05)

There’s no denying the artistry. But it’s important to name what often goes unspoken: the dis imbalance. For decades, the canon of “feminine” design has been mediated through a masculine lens. The woman is muse, but never the maker. She is adorned and idealized, her form being a site of inspiration but never authorship. The result is an aesthetic culture where “feminine” becomes something bestowed upon her by a man with taste.

This isn’t to say male designers cannot or should not design for women, many do so with skill, care, and great sensitivity. But sensitivity alone doesn’t negate the deeper historical dynamic at play, where fashion morphs into a stage for projection, and the female form a canvas for the male fantasy. The clothes may flatter, but they also dictate, and silence. A nipped waistline is a command, not a mere suggestion.

(Courtesy of Tom Ford)

The language used to describe the work of prominent male designers often leans toward the sensual, carnal, and even erotic. Garments are depicted by the media as “caressing,” “sculpting,” “embracing” the body. Runway shows are framed as love letters to women. But there’s a fine line between what seems like adoration and possession. At what point does knowing how to dress a woman become a way of controlling her image?

When a man’s ability to capture femininity is seen as genius, it raises the question: what happens when women design for themselves? Often, the reception is different. Female designers are lauded for realism, for pragmatism, for designing with the lived female experience in mind. But rarely are they mythologized as visionaries in the same way men are. Their work is often described in terms of function and empowerment as opposed to fantasy. They are applauded for what they remove, inconvenient heels, overly-restrictive boning, unnecessary flourishes, rather than what they add. While men are praised for elevating the female form, women are praised for liberating it. And buried in that disjunction is a hierarchy.

The romanticization of the male gaze in fashion doesn’t begin or end with design. It’s also embedded in the way collections are covered as well as remembered. Male designers are given credit for “understanding women,” while female designers are expected to simply be women. The bar is different, and the narrative, predetermined.

(Oscar De La Renta – 1984)

This isn’t an indictment of talent necessarily, it’s a call for nuance. Admiration need not be blind. Acknowledging the layers of control and projection in fashion history doesn’t make the work less beautiful. It makes our understanding of it more complete. There is room to appreciate a McQueen gown and still recognize the violence it has the potential to evoke. There is space to admire Dior’s architectural brilliance while interrogating the ideals it reinforced.

(Courtesy of The Cut Magazine)

Today, as conversations about gender, power, and innovation reshape the fashion landscape, we’re beginning to see shifts. More female designers are rising to prominence, telling stories that aren’t shaped by how they look but how they see. Designers like Simone Rocha, Marine Serre, and Cecilie Bahnsen aren’t just making “women’s clothes”, they’re expanding the visual vocabulary of what femininity can look and feel like. There’s a softness, yes, but also volume, chaos, asymmetry, and distortion. Their work doesn’t seek to flatter in the traditional sense. It conflicts. And in doing so, it liberates the female identity.

The history of fashion is filled with beauty. But it is also filled with myth. The idea that femininity is best understood from the outside is one of them. Perhaps the true evolution of womenswear lies not in rejecting the male gaze entirely, but in recognizing its place, and moving beyond it. Femininity is not a formula. It’s not a waistline, or a neckline, or a hem. It’s not something designed for her. It’s something designed by her.