The Male Gaze in Stitching

Credit: Courtesy of Vogue

The Male Gaze in Stitching

All eyes turned to Paris this week as Jonathan Anderson presented his debut collection for the Dior house. His runway looks certainly did not disappoint, as he seamlessly combined slouchy silhouettes with more structured shapes, successfully introducing a freshness while respecting the label’s classicism. We saw popped collars. Pops of color. And a roar in pop culture. But beneath all the praising reviews (and trust me, I have plenty), I can’t help but think about the implications behind yet another man in the position of creative director, especially at a house so synonymous with femininity. When Anderson picks up the thread and needle at Dior, he inherits more than just a brand. He stitches into a gaze. After all, fashion is more than just fabric. It’s power, storytelling, and a question of who gets to hold the needle. It’s empathy, or often, the lack of it.

First coined by film theorist Laura Mulvey in 1975, the term “male gaze” refers to a lens constructed by the masculine perspective, portraying women as sexual objects for the pleasure of the male viewer rather than agents of their own stories. In fashion, this gaze takes many forms—from stitching to styling to runway. No matter the stage, the question remains the same: are women just passive subjects of men’s desires? Or can men truly design for women, stepping into the female shoes (or in this case, heels)?

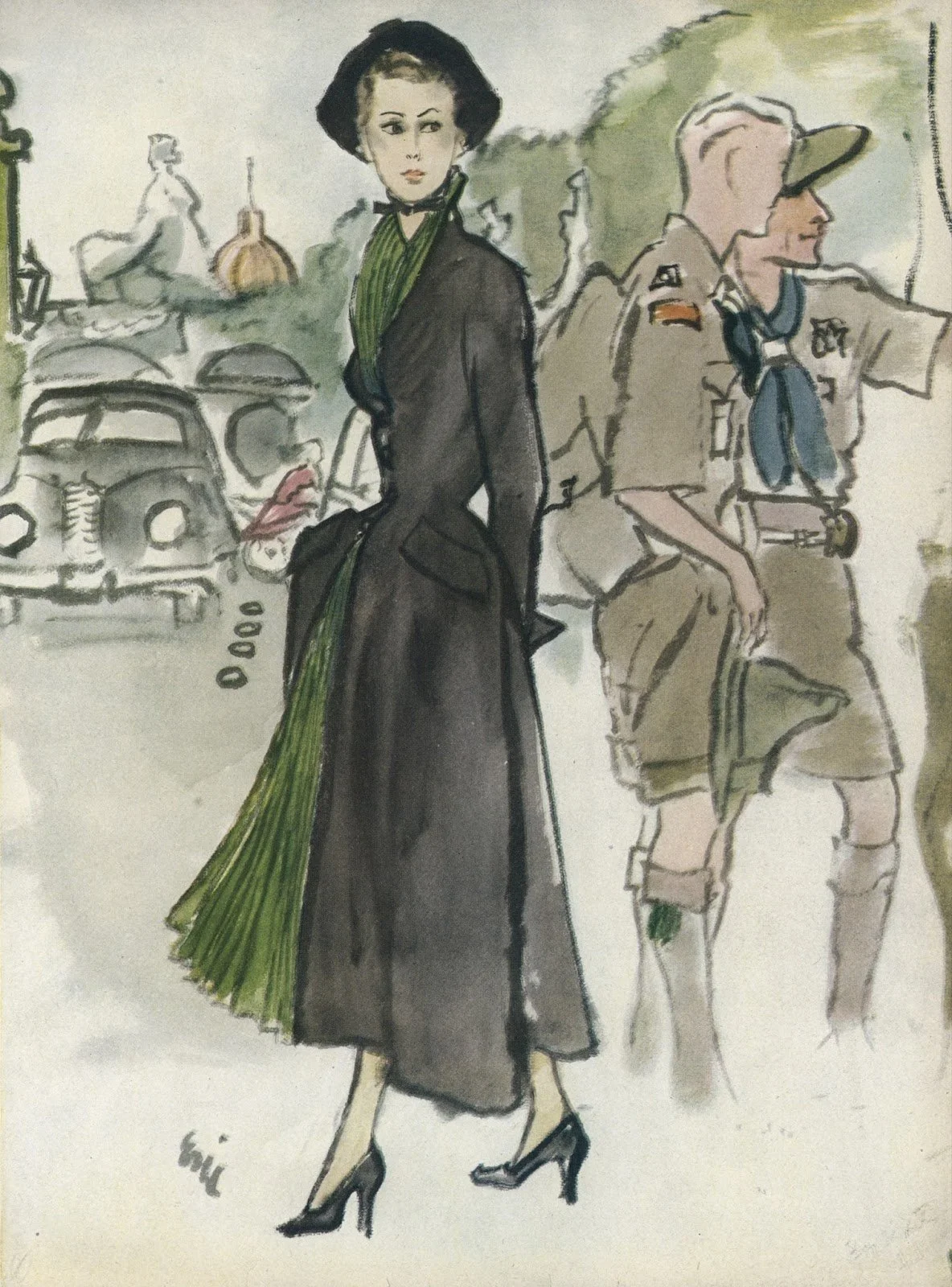

He Sketched, She Wore

Since 1946, Dior has been a house largely shaped by men. Built on the bones of Christian Dior’s “New Look”, a silhouette that cinched women into an idealized version of themselves, the label has consistently provided an interpretation of the modern woman. Christion Dior introduced the “New Look” post World War II when women in France were exceptionally thin. In crafting voluminous shapes and cinched waists, he wasn’t just designing clothing, but rather, offering a vision of restoration. For his sister Catherine, a concentration camp survivor, the act of wearing a full, structured dress was more than an aesthetic—it was a symbol. To look in the mirror and see a new body was, in its own way, a gesture of hope. After Christian Dior, a long thread of male creative directors—Yves Saint Laurent, Marc Bohan, Gianfranco Ferré, John Galliano, Raf Simons, and more—continued to use fashion as a tool for storytelling through women’s bodies.

Credit: Courtesy of Vogue

Stitching From the Inside Out

Seventy years later, Maria Grazia Chiuri picked up the needle at the Dior house. In an interview with The Guardian, she laughed about the surprise that greeted “the first woman in charge,” but disclosed a harsher truth: “It’s very hard for women to arrive in positions of power,” she said. “The narrative is always that the geniuses are men.” Chiuri’s tenure, while at times polarizing, undoubtedly delivered something new to the label, disrupting Dior’s long-established “male gaze”. She designed not through women but for women, and in stitching, drew from lived experiences to tell a narrative from the inside out.

Credit: Courtesy of Pascal Le Segretain

Now, Anderson succeeds Chiuri as the creative director for the women's collection. Though his work for women is yet to be unveiled, attendees of the men’s show in Paris offered a preview of what’s to come. Sabrina Carpenter appeared in a “New Look”–inspired ensemble, an ode to Dior’s 1947 origins. Yet, I can’t help but feel there was nothing truly new about it. The 1940s were a long time ago. Christian Dior’s story has been told. It isn’t the story women are asking to anymore.

Credit: Courtesy of Getty Images

Jonathan Anderson, by all accounts, is creative, thoughtful, and remarkably skilled. His debut proves he can honor legacy with true Andersonian panache, abiding by house codes while still introducing surprise. But empathy isn’t creativity—it’s embodiment.

The Canvas or the Subject?

For an industry so deeply embraced, shaped, and supported by women, the fashion realm still offers far too many opportunities to men. Men decide how women dress and present their bodies to the world. Runways are directed through a male lens—one that, whether consciously or not, treats the female body as a canvas to style rather than a nuanced, breathing entity.

What’s especially jarring is to think about how much control men have over something so representative of me. My body. My identity. My expression. Yes, I believe a male director can “empathize”. He can admire, interpret, and attempt to tell the story. Christian Dior, for example, “empathisized” with his sister. But a male director cannot fully tell the female story because he will never truly live it. He will never walk in her shoes. He will never understand her body—how it changes from month to month and from year to year. He won’t feel the emotions she feels or the societal expectations that fall upon her. He can’t experience the gaze. Disguised as a celebration of femininity, it’s still the male gaze that crafts the narrative.

So while I genuinely admire Anderson’s work and look forward to this new chapter at Dior, I can’t help but feel a quiet disappointment at the continued lack of female representation in creative leadership. If we want fashion to reflect real women, we need more women telling the story. It’s time we stop asking whether men can do it, and start asking why women still have to wait their turn. We need more women at the top. Point blank.